Research

My main Research Interests are in:

- Partial Differential Equations

- PDEs with random coefficients. Limiting models.

- Wave Propagation in highly heterogeneous media and Kinetic Models. Applications to Imaging and Time Reversal.

- Deterministic and Monte Carlo simulations of Transport Equations

- Partial differential models of Topological Insulators and Edge Transport.

- Theory of Inverse Problems

- Hybrid Inverse Problems. Photo-acoustic Tomography and Ultrasound Modulation Tomography.

- Inverse Transport Theory. Application to X-Ray Tomography, Optical Tomography and Remote Sensing

- Random correctors & Inverse Problems.

- Calderón Prize Lecture for the 2011 Calderón Prize given by the Inverse Problems International Association (IPIA)

- Introduction to Inverse Problems : Lecture Notes from graduate courses offered at Columbia, the University of Chicago, and various Summer Schools.

- Slides : from AIP summer school with some Mathematical supplements .

Below are brief descriptions of current research areas of interest and related papers.

Topological Insulators (TI) and Edge transport

Asymmetric edge transport and topological obstruction to Anderson localization

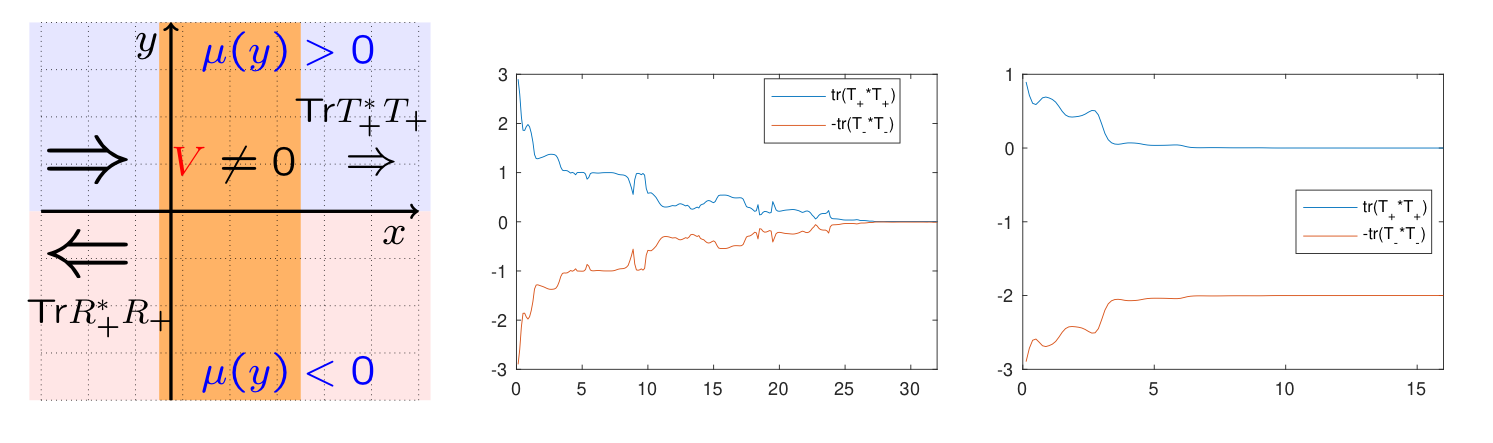

TIs are insulating systems whose macroscopic properties can be described by a Topological invariant (the topological phase of the system). Arguably the most important practical property of TIs occurs at interfaces separating insulating systems in different topological phases. Currents propagate along the waveguide created by the interface and enjoy surprising `topological protection'. A striking feature of such edge currents is their asymmetric (chiral) nature: propagation is different in both directions. Moreover, the feature persists even in the presence of strong randomness (e.g., defects). In some cases, propagation is observed in only one direction, even in the presence of defects. This absence of back-scattering, which is not of purely topological origin, is very appealing in applications, for instance in communication, and is one of the main reasons for the rapidly increasing list of papers available on the topic. Many theoretical and experimental results have now appeared in the physical and engineering literatures, with a growing number of results in the mathematical literature as well.A comment that sometimes appears in the literature asserts that the absence of back-scattering is 'protected topologically'. The paper Topological protection of perturbed edge states [B. Comm. Math. Sci. 2019] revisits this question. This paper introduces a class of two-dimensional Hamiltonians to describe transport in the vicinity of a vertical edge of interest parametrized by \(x=0\). An analytic Noether (Fredholm) index is assigned to each Hamiltonian in the form \(M_\tau-N_\tau\), which can be related to the difference of topological invariants (Chern numbers) of the bulks on the left and right of the edge.

A scattering theory next quantifies transport along the vertical edge \(x=0\). We analyze the influence of the non-trivial topology on the scattering coefficients. In particular, we show that transmission in one direction is bounded from below by \(M_\tau-N_\tau\geq0\) independent of the strength of random perturbations. This provides a surprising obstruction to Anderson localization. Moreover, such an obstruction is quantized. For an appropriate model of random fluctuations, we show that in the presence of strong perturbations, transmission is asymptotically given by \(M_\tau-N_\tau\). This implies that a number \(M_\tau-N_\tau\) of randomness-dependent modes transmit through the random medium while all other modes (asymptotically) purely reflect. Transmission in the opposite direction is asymptotically also suppressed, as expected from Anderson localization; see figure below.

Asymmetric transport requires systems that break time reversal symmetry. For time-reversal symmetric materials, \(M_\tau-N_\tau=0\) necessarily. For systems satisfying a Fermionic Time Reversal Symmetry (FTRS; typically valid in electronic systems), involving an anti-Hermitian operator \({\cal T}\) such that \({\cal T}^2=-1\), the above results extend to the setting where a \({\mathbb Z}_2\) index is defined as \( M_\tau{\rm mod } 2\). When \(M_\tau\) is odd, the system is topologically non-trivial and non-trivial transmission is guaranteed in both directions, again as a violation of Anderson localization. When \(M_\tau\) is even, the FTRS is not sufficiently strong to prevent mode coupling and complete Anderson localization in the presence of strong fluctuations.

Quantitative edge transport, integral formulations, time-dependent picture

The analysis of transport along interfaces separating insulating bulks leads to a number of natural questions. The first one is related to its scattering theory. A central element of scattering theory analyzes the influence of localized perturbations on unperturbed plane waves (generalized eigenfunctions). Significantly less is known in the setting of waveguides compared to full space scattering such as perturbations of the Laplace operator. In Scattering theory of topologically protected edge transport, we apply a limiting absorption principle to perform such analyses. This allows us to define scattering operators and links the asymmetric edge transport to scattering data.Beyond their topological properties, there is also considerable interest to obtain quantitative estimates of such interface transport. This led to the development of integral formulations for the interface problem. An integral formulation analyzing volumetric perturbations of a Dirac model is presented in Asymmetric transport computations in Dirac models of topological insulators [B. Hoskins Wang, J. Comp. Phys. 2023]. The numerical framework was generalized to \({\mathbb Z}_2\) invariants in \({\mathbb Z}_2\) classification of FTR symmetric differential operators and obstruction to Anderson localization. The latter work also revisits quantitative obstructions to Anderson localization and shows for a large class of problems that the \({\mathbb Z}_2\) index is non-trivial if and only if edge transport cannot be gapped by continuous deformations.

Integral formulations for Klein Gordon and Dirac operators with piece-wise constant coefficients are introduced in Integral formulation of Klein-Gordon singular waveguides and in Integral formulation of Dirac singular waveguides, respectively. These formulations provide an interesting theoretical tool to analyze interface scattering problems and an incredibly efficient one to simulate them numerically.

The construction of topological invariants for interface Hamiltonians is purely spectral. Topological invariants are typically constructed to be immune to (spatially) compactly supported perturbations. This robustness to such deformations heuristically means that topology encodes large scale features. Such features cannot be tested by (finite) time dependent problems that typically probe a bounded part of the Euclidean plane. Yet, localized wavepackets are still expected to reflect the non-trivial topology of the system they probe. This behavior is analyzed in a series of recent papers devoted to the propagation of wavepackets localized near an interface separating insulators in the semi-classical regime; see Edge state dynamics along curved interfaces [B. Becker Drouot Fermanian-Kammerer Lu Watson SIMA 2023], Magnetic slowdown of topological edge states [B. Becker Drouot CPAM 2023], as well as Semiclassical propagation along curved domain walls [B. MMS 2023].

Classification by domain walls and Bulk-Edge Correspondence

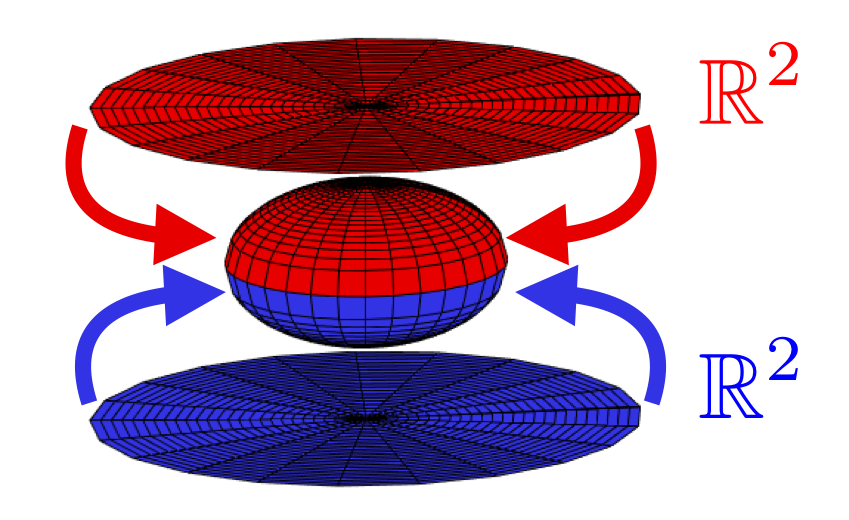

The results mentioned above involve continuous partial (or pseudo) differential models in the Euclidean plane. Because the dual/reciprocal space is itself the Euclidean plane, and hence unbounded, standard constructions of invariants on compact manifolds, such as Chern numbers or winding numbers, do not apply in general. The paper Continuous bulk and interface description of topological insulators [B. J. Math. Phys. 2019] revisits this question specifically for bulk and interfaces TIs modeled by systems of Dirac equations in Euclidean spaces of arbitrary dimension. Using notions of Fredholm modules introduced in earlier works by Atiyah and Connes and used in the context of topological phases in theories of the Integer Quantum Hall Effect by Bellissard and Avron-Seiler-Simon, Dirac systems are mapped to Fredholm operators by spectral calculus. The resulting index is then shown to be stable against classes of random perturbations using standard tools in functional calculus and the Helffer-Sjöstrand formula.In order to model asymmetric transport for more general models than Dirac systems, we first need a physical observable that characterizes such transport. The following observable, first introduced in work by Schulz-Baldes and collaborators and work by Graf and collaborators, is now ubiquitous, in a form or another, in mathematical analyses of edge transport: \[ \sigma_I = {\rm Tr} \ i[H,P] \varphi'(H). \] Here, \(H\) is the Hamiltonian of interest, \(P=P(x)\) is intuitively a function equal to \(1\) for \(x>x_0\) and equal to \(0\) otherwise (the plane is parametrized by \((x,y)\)). The operator \(i[H,P]\) then affords an interpretation as a current operator (amount of signal propagating from the left to the right of the line \(x_0\) per unit time). The function \(\varphi'(H)\geq0\) and integrating to \(1\) should be interpreted as a density of states selecting an energy (or frequency) range of excitations that cannot propagate into the insulating bulks. Thus, \(\sigma_I\), with \({\rm Tr}\) operator trace on \(L^2\), is the expected value of the operator \(i[H,P]\) for the density of states \(\varphi'(H)\geq0\). It turns out that \(\sigma_I\) is quantized in many settings of interest. Moreover, if \(I^N\) and \(I^S\) are two bulk invariants associated to the two insulators north and south of the interface \(\{y=0\}\), then the Bulk-Edge Correspondence states after appropriate orientation that \[ 2\pi \sigma_I = I^N-I^S \in {\mathbb Z}. \] The bulk edge correspondence is a central principle in the physical interpretation of topological insulators. Its derivation remains difficult independently of the context in which it applies. Most works on the bulk-edge correspondence in fact relate edge transport along a boundary to the bulk invariant in the volume (say \(I^N\) with then \(I^S\) set to \(0\)). It has been derived rigorously mathematically in many discrete settings, using either algebraic K-theory techniques generalizing Belissard's original work or more analytical techniques generalizing the Avron-Seiler-Simon theory. It was also generalized to continuous settings where bulk invariants are naturally defined.

For many differential problems, including the ubiquitous systems of Dirac equations, \(I^N\) or \(I^S\) are not naturally defined. However, their difference \(I^N-I^S\), the only quantity that appears in the bulk edge correspondence, often makes sense as a Bulk-difference invariant. This reflects a well-known fact that (topological) phase differences are defined more generally than absolute phases.

A general classification of elliptic partial differential operators and a derivation of the bulk-edge correspondence in this setting is proposed in the papers Topological invariants for interface modes [B. Comm. PDE 2022], generalized in Approximations of interface topological invariants [Quinn B. SIMA 2024], and extended to arbitrary dimension (and Higher-Order Topological Insulators) in Topological charge conservation for continuous insulators [B. J. Math. Phys. 2023]. The salient features of the results in these papers is summarized as follows.

For \(H_k\) an elliptic operator assumed to be confined in \(0\leq k\leq d-1\) dimensions in a \(d-\)dimensional Euclidean space, the two operator \[ H_{d-1} = \gamma_0 \otimes H_k + \mu(x) \cdot \gamma \otimes I,\quad \mbox{ and } \quad F = H_{d-1} -i\mu(x_d), \] are constructed using known Clifford matrices \(\gamma_0\) and \(\gamma\) and domain walls \(\mu(x)\). The operator \(H_{d-1}\) is an interface Hamiltonian similar to the ones described above when \(d=2\). The main advantage of the procedure is that \(F\) is a Fredholm operator. Writing \(F={\rm Op}^w a\) with \(a\) the matrix-valued Weyl symbol of \(F\), which may be written explicitly in terms of the Weyl symbol of the initial operator \(H_k\), we associate to \(H_k\) the topological invariant \[ {\mathbb Z} \ni {\rm Index} \,F = - \frac{(d-1)!}{(2\pi i)^d (2d-1)!} \int_{{\mathbb S}^{2d-1}_R} {\rm tr}\, (a^{-1} da)^{\wedge(2d-1)}. \] Here, \(R\) is chosen large enough that \(a^{-1}\) is defined outside of the ball of radius \(R\) (in phase space). This is the Fedosov-Hörmander formula, which implements in Euclidean spaces an Atiyah-Singer index theory.

This invariant is defined for a large class of Hamiltonians \(H_k\) as a generalized winding number of its Weyl symbol. It is also defined for non-Hermitian operators \(H_k\) so long as \(a^{-1}\) is indeed defined as above. It may thus also serve to classify non-Hermitian operators (in the symmetry classes A and AIII).

For Hermitian operators, the above papers prove a Bulk-Edge Correspondence of the form: \[ \mbox{ Theorem (Generalized Bulk-Edge Correspondence)}: \quad 2\pi \sigma_I[H_{d-1}] = {\rm Index} \,F. \] In dimension \(d=2\) with interface Hamiltonian \(H=H_1\), the above formula simplifies as an application of the Stokes theorem (since \(d{\rm tr}\,(a^{-1}da) ^{\wedge 3} =0\)) to \[ 2\pi \sigma_I[H] = {\rm Index} \,F = \frac{1}{24\pi^2}\int_{{\mathbb S}_R^3} {\rm tr}\ (a^{-1}da) ^{\wedge 3} = \frac{1}{24\pi^2}\int_{\{y=R\} \cup \{y=-R\}} {\rm tr}\ (a^{-1}da) ^{\wedge 3}. \] In other words, the edge current observable \(2\pi \sigma_I[H] \), which is a priori difficult to compute, simply depends on the symbol of \(H\) in the insulating bulks (at \(y=\pm R\)). This remarkable identity, which is natural in light of the Atiyah-Singer index theory, allows one to considerably simplify the computation of the edge invariant as a simple integral.

The integral further simplifies assuming bulk Hamiltonians invariant under translation for \(|y|\) sufficiently large. Writing phase space in the variables \((x,y,\xi,\zeta)\), we may introduce

\[

{-a(\omega,y=\pm R,\xi,\zeta) = (i\omega- \hat H_B^{N/S}(\xi,\zeta)) ,\qquad \Pi^{N/S}(\xi,\zeta)=\chi(\hat H_B^{N/S}(\xi,\zeta)<0)} .

\]

Here, \(\Pi^{N/S}(\xi,\zeta)\) are families of projection operators onto the negative spectrum of the (North and South) bulk Hamiltonians \(\hat H_B^{N/S}(\xi,\zeta)\) in Fourier variables. We then show that

\[

2\pi\sigma_I= \frac{i}{2\pi} \int_{{\mathbb R}^2} {\rm tr} \big( \Pi^S[\partial_1 \Pi^S,\partial_2\Pi^S] - \Pi^N[\partial_1 \Pi^N,\partial_2\Pi^N]\big) d\xi d\zeta

\]

written as Bulk-difference invariant. The above expression follows the standard construction of Chern numbers on the unit sphere obtained by circle compactification of the two Fourier planes.

Bulk-Edge Correspondence (or not), spectral flows, and ellipticity

While the bulk-edge correspondence applies to general (appropriately gapped) discrete systems, the above derivation requires Hamiltonians to satisfy an ellipticity constraint. In the absence of such an ellipticity constraint, the above Fedosov-Hörmander formula is unlikely to apply. However, in many situations, an alternative expression for the edge current is available: \[ 2\pi\sigma_I = {\rm SF}[H] \] where SF stands for spectral flow of the branches of absolutely continuous spectrum of \(H\) restricted to the support of the density \(\varphi'(H)\). See the aforementioned papers for a derivation. This relation to the spectral flow allows one to compute the edge current in the presence of bulk flat bands, and hence for Hamiltonians that are not elliptic. Such Hamiltonians are also ubiquitous, with applications in magnetic Schrödinger and magnetic Dirac operators and in shallow water models of atmospheric transport. This relation was used in Asymmetric transport for magnetic Dirac equations [Quinn B. PAA 2024] to derive a form of bulk-edge correspondence for magnetic Dirac operators involving domain walls in their electric and magnetic potentials and in their mass terms.Note that the Fedosov-Hörmander formula provides a significantly simpler means to compute the edge current \(2\pi\sigma_I \) than the spectral flow \({\rm SF}[H]\), which requires a complete diagonalization of the operator \(H\) restricted to the support of \(\varphi'(E)\).

The same notion of spectral flow has been used in the analysis of asymmetric atmospheric mass transport along the earth's equator, which was given a topological interpretation in a 2017 Science paper by Delplace-Marston-Venaille. The insulating bulk phases result from a Coriolis force parameter that is non-vanishing in the northern and southern poles but changes signs in the vicinity of the equator. This model involves a flat band (infinitely degenerate point spectrum at frequency \(E=0\)).

Surprisingly, the bulk-edge correspondence does not fully apply in that setting in the sense that the current observable \(2\pi\sigma_I = {\rm SF}[H]\) depends on the way the Coriolis force parameter transitions from the Northern to the Southern hemispheres. In particular, when the Coriolis force parameter is proportional to the latitude variable \(y\), then \(2\pi\sigma_I = {\rm SF}[H]=2\), which is the `correct' value we expect from the bulk-edge correspondence. In contrast, we observe that \(2\pi\sigma_I = {\rm SF}[H]=1\) when the Coriolis force parameter equals the sign function of \(y\). See [B. Comm. PDE 2022] and [Quinn B. SIMA 2024] for details. A forthcoming work in collaboration with Jiming Yu shows that \(2\pi\sigma_I\) may in fact take any value in \({\mathbb Z}\) for discontinuous profiles of the Coriolis force parameter. However, when the latter is sufficiently smooth, then \(2\pi\sigma_I=2\) as per the bulk-edge correspondence.

Hybrid Inverse Problems.

Optical tomography (see below) and Electrical Impedance Tomography are useful modalities thanks to the large contrast often observed between the optical and electrical properties of healthy and non-healthy tissues. However, because of multiple scattering, these are low-resolution modalities.Ultrasound tomography enjoys high resolution capabilities. However, because sound speeds vary little between healthy and non-healthy tissues, it is low-contrast.

One way to combine large contrast and high resolution is to use the photo-acoustic effect: as (near-infra-red or electromagnetic) radiation propagates through a medium of interest, partial absorption causes thermal expansion and the generation of ultrasound. Such ultrasonic waves propagate to the domain's boundary where they are measured. See the Wikipedia web page. The amount of absorbed radiation is first reconstructed by solving an inverse wave source problem. Next comes the problem of Quantitative Photo-Acoustic Tomography (QPAT) where the optical parameters are reconstructed from knowledge of the absorbed radiation map.

Mathematically, these inverse problems involve parameter reconstructions from knowledge of Internal Functionals. Such inverse problems are often referred to as Hybrid Inverse Problems, or alternatively Coupled-Physics Inverse Problems or Multi-Waves Inverse Problems.

For recent results on QPAT and the related quantitative Thermo-acoustic Tomography (QTAT), see the papers Inverse Diffusion Theory of Photoacoustics (with G. Uhlmann), Inverse Problems, 26(8), 085010, 2010; Inverse Transport Theory of Photoacoustics (with A. Jollivet and V. Jugnon), Inverse Problems, 26, 025011, 2010; On Multi-spectral quantitative photoacoustic tomography (with K. Ren), Inverse Problems, 27(7), 075003, 2011; Quantitative Thermo-acoustics and related problems (with K. Ren, G. Uhlmann and T. Zhou), Inverse Problems 27(5), 055007, 2011; as well as Multiple-source quantitative photoacoustic tomography (with K. Ren), Inverse Problems 28(1), 025010, 2012.

More generally, QPAT, QTAT, as well as the elasticity-based modalities Transient Elastography (TE) and Magnetic Resonance Elastography (MRE) all involve reconstructions of parameters in the elliptic equation \[\nabla\cdot a\nabla u+b\cdot\nabla u+cu=0\] from knowledge of internal functionals of the form \[H(x)=u(x) \quad \mbox{ or } \quad H(x) = \Gamma(x) u(x) \] for some typically unknown function \(\Gamma(x)\). The analysis of what can and cannot be reconstructed in the possibly complex-valued \((a,b,c)\) for \(a\) possibly tensor-valued from knowledge of functionals of the form \(H(x)\) is analyzed in Reconstruction of coefficients in scalar second-order elliptic equations from knowledge of their solutions (with G. Uhlmann), arXiv:1111.5051.

Another hybrid imaging methodology is Ultrasound Modulated Optical Tomography, also called acousto-optics. In this setting, acoustic waves are emitted to change the index of refraction and the spatial density of the absorbers and scatterers. Light propagating through the medium is influenced by these changes and provides local information about the optical parameters. See the model described in Inverse Scattering and Acousto-Optic Imaging (with J.C. Schotland), Phys. Rev. Letters, 104, 043902, 2010. Mathematically, these inverse problems correspond to solving 0-Laplacians from possibly redundant power density measurements of the form \[H_{ij}(x)=\gamma(x) \nabla u_i(x)\cdot\nabla u_j(x)\] for \(u_i(x)\) solution of the elliptic equation \(\nabla\cdot \gamma\nabla u_i=0\) with appropriate conditions \(u_i=g_i\) at the boundary of the domain of interest. Because the direction of \(\nabla u_j\) is not available in such measurements, the analysis of such hybrid inverse problems is significantly more complex than for functionals of the form \(H(x) = \Gamma(x) u(x)\).

Recent results on the problem are reported in Cauchy problem for Ultrasound Modulated EIT , To Appear in Analysis and PDE; Inverse diffusion from knowledge of power densities (with E. Bonnetier, F. Monard and F. Triki), submitted; and Inverse diffusion problem with redundant internal information (with F. Monard), submitted. The reconstruction of an anisotropic diffusion tensor \(\gamma\) from such functionals was recently analyzed in two space dimensions in Inverse anisotropic diffusion from power density measurements in two dimensions (with F. Monard), submitted.

A recent review paper on Hybrid Inverse Problems is available at Hybrid inverse problems and internal information (review paper), to appear in Inside-Out, Cambridge University Press, 2012 (G. Uhlmann editor).

The Calderón Prize lecture given during AIP 2011 at Texas A& M is available at Inverse Problems with Internal Functionals. From Calderón's problem to Hybrid Inverse Problems .

Limiting models for Equations with stochastic coefficients.

Many results of homogenization for equations with random coefficients have been obtained over the past decades. In such theories, random solutions are shown to be accurately approximated by deterministic, effective medium solutions. Of considerable interest in many applications, including in solving inverse problems and/or parameter estimation problem, is the characterization of the random fluctuations in the solution. Such a characterization is understood in an extremely limited number of cases.What the random fluctuations look like and what they depend upon is analyzed in a series of papers Central limits and homogenization in random media, (long version with more detailed proofs arXiv:0710.0363 ), Multiscale Model. Simul., 7(2), pp. 677-702, 2008; Random integrals and correctors in homogenization (with J. Garnier, S. Motsch, and V. Perrier), Asymptotic Analysis, 59(1-2), pp. 1-26, 2008; Corrector theory for elliptic equations in random media with singular Green's function. Application to random boundaries (with W. Jing), Comm. Math. Sci., 9(2), pp. 383-411, 2011; Corrector Theory for Elliptic Equations with Long-range Correlated Random Potential (with J. Garnier, W. Jing, and Y. Gu), to appear in Asymptotic Analysis.

These papers show that the size of the random fluctuations of the elliptic solution strongly depend on whether the random parameters are short-range or long-range. The random fluctuations also need not be asymptotically Gaussian as is shown in Random Homogenization and Convergence to Integrals with respect to the Rosenblatt Process (with Y. Gu), submitted.

Consider the parabolic Anderson model \[ \partial_t u_\varepsilon + (-\Delta)^{\frac m2} u_\varepsilon + \frac{1}{\varepsilon^\alpha}q(\frac x\varepsilon) u_\varepsilon =0\] for \(\alpha\) chosen so that the large but rapidly oscillating (Gaussian) potential \( q \) has a strong influence on \(u_\varepsilon\). Then the behavior of \(u_\varepsilon\) as \(\varepsilon\to0\) depends on spatial dimension.

In dimensions \(d\geq m\), we obtain in the limit a homogenized, deterministic equation as is shown in: Homogenization with large spatial random potential, Multiscale Model. Simul., 8, pp. 1484-1510, 2010.

In smaller dimensions \(d < m\), the solution to the equation with heterogeneous coefficients does not converge to a deterministic equation but rather to a stochastic partial differential equation (SPDE) with multiplicative noise as is shown in: Convergence to SPDEs in Stratonovich form, Comm. Math. Phys., 212(2), pp. 457-477, 2009.

The generalization to long-range, possibly time-dependent, potentials is analyzed in: Convergence to Homogenized or Stochastic Partial Differential Equations, Appl Math Res Express, 2011(2), pp. 215-241, 2011.

There are several applications to the macroscopic modeling of the random fluctuations of PDE solutions. One such application is the derivation of physics-based noise models in Inverse Problems; see below.

An other application pertains to the testing of numerical multi-scale algorithms. We can then ask ourselves whether in a well-understood environment, the random fluctuations generated by the algorithm are accurate discretizations of the random fluctuations of the continuous model; see Corrector theory for MsFEM and HMM in random media (with W. Jing), Multiscale Model. Simul., 9, pp. 1549-1587, 2011, for an analysis in the (already technically challenging) one-dimensional setting.

Kinetic Models and Imaging.

As waves propagate through heterogeneous media, they scatter and their energy may change direction. An accurate macroscopic description of such phenomena is obtained by using kinetic models to represent the energy density of the propagating waves. Kinetic models more generally may be used to track the correlation of two wave fields propagating in possibly different heterogeneous media. Here is the paper Kinetics of scalar wave fields in random media on the subject. Kinetic models have also been validated numerically (with Olivier Pinaud) in Accuracy of transport models for waves in random media. In statistically stable random media, i.e., in media in which the energy density can be shown to depend weakly on the specific realization of the random media, the kinetic models may be used to detect and image buried inclusions in a cluttered environment. I refer, e.g., to the paper Self-averaging in time reversal for the parabolic wave equation (written with George Papanicolaou and Lenya Ryzhik) for work on the statistical stability of waves in random media. [Note that waves are not always stable as was shown in the paper: On the self-averaging of wave energy in random media.] References on Imaging in random media using kinetic models may be found in a series of papers: Kinetic Models for Imaging in Random Media (with Olivier Pinaud) and Transport-based imaging in random media (with Kui Ren). Results on kinetic-based reconstructions from experimental data (collected in Larry Carin's group at Duke University) may be found Experimental validation of a transport-based imaging method in highly scattering environments (written with Larry Carin, Dehong Liu, and Kui Ren).Time Reversal.

Theoretical understanding. Time reversal consists of understanding why time-reversed waves propagating in highly heterogeneous media refocus much more tightly at their original location than when they propagate in a homogeneous medium. A numerical simulation demonstrating the effects of time reversed wave pulses propagating in random media can be seen on this web page. The reason for the very good refocusing observed in heterogeneous media and absent in homogeneous media is multiple scattering. Multiple interactions of waves with the underlying structure can be modeled in several ways. Radiative transfer models are multi-dimensional models that accounts very well for the spatial multiple scattering observed in physical experiments. Our quantitative analysis of time reversal refocusing can be found in the paper: Time Reversal and refocusing in Random Media.Changing media. In many practical applications, the media during the forward and backward stages of the time reversal experiment may slightly (at best) differ. We have shown in the paper Time Reversal in Changing Environment, how the refocusing of the time reversed signal is affected by changes in the underlying media. How much can media change before time reversed waves lose their enhanced refocusing properties? Our answer is: very little. A mathematical analysis in the simplified setting of paraxial approximations may be found in the following paper with L. Ryzhik: Stability of time reversed waves in changing media.

Detection and Imaging. Several studies have recently been conducted to understand how the refocusing properties of time reversed waves may be used in detection and imaging in heterogeneous media. Unless the underlying propagating media is known (or the available approximation correlates very closely with the exact media, which is seldom the case in applications) time reversal and imaging live in different worlds. In the former, the time reversed signal back-propagates through the real physical media whereas in the latter, its propagation must be simulated on the computer, whence in a very different manner. In a recent paper with Olivier Pinaud, Time reversal based detection in random media, we show that time reversal may still be used in detection and imaging in highly heterogeneous media provided that the underlying media is known statistically (which is much easier to get than full knowledge) and statistically stable, which is arguably the main hindrance to successful detection and imaging in heterogeneous media. Reconstructions based on experimental data (collected by Larry Carin's group at Duke University) may be found in Electromagnetic Time-Reversal Imaging in Changing Media: Experiment and Analysis.

Links to Talks and Lecture Notes

Here is a link to the presentation (20Mb file with movies) given at the AIP 2007 in Vancouver in the summer of 2007.Here is a two-hour talk given at the end of a course on "Waves in Random Media", two tutorial lectures ( Lecture 1; Lecture 2) given in September of 2005 at the CIRM, Luminy, France, and a fairly long presentation given in the fall of 2003 at IPAM, on wave propagation in random media and time reversal.

Here is a link to Lecture Notes for a course on waves in random media given at Columbia in the fall of 2005.

Inverse Transport Theory.

Transport equations are ubiquitous in medical and geophysical imaging. Scattering-free transport equations model high-energy particles propagating through human tissues, as in X-Ray Tomography. Lower frequency (near-infra-red) photons as used in Optical Tomography are modeled by transport equations with large scattering coefficients.Inverse transport theories strongly depend on the amount of scattering in the forward transport equation. In highly scattering environments, inverse transport is replaced by inverse diffusion problems, which are well-studied. In the absence of scattering, inverse transport is an integral geometry problem, which is also well understood. Inverse transport bridges the gap between the two regimes. See the paper Inverse Transport Theory and applications (review paper), Inverse Problems, 25, 055006, 2009, for a review of recent results obtained in inverse transport theory.

A major difficulty in inverse transport theory is to understand which optical properties of the underlying medium may be stably reconstructed. This crucially depends on the source (isotropic versus angularly resolved) and on the measurements (time dependent or not, angularly resolved or angularly averaged). Here is a sequence of recent papers on this topic. Time-dependent angularly averaged inverse transport (with A. Jollivet), Inverse Problems, 25, 075010, 2009. (long version with additional proofs and results arXiv:0902.3432 ) ; Approximate stability in inverse transport (with A. Jollivet), in Biomedical Mathematics, Ed. Y. Censor, M. Jiang, G. Wang, Medical Physics Publishing, Wisconsin, 2010; Stability for time dependent inverse transport (with A. Jollivet), SIAM J. Math. Anal., 42(2), pp. 679-700, 2010; Inverse transport with isotropic sources and angularly averaged measurements , (with I. Langmore and F. Monard), Inverse Probl. Imaging, 2(1), pp. 23-42, 2008

Here is a sequence of three talks ( Lecture 1, Lecture 2, Lecture 3) given on the subject at the University of Washington during the Summer School organized in August 2005 by Gunther Uhlmann.

Ray transforms and X-Ray Tomography.

X-Ray tomography (or computerized tomography) is ubiquitous in medical imaging. Not surprisingly, it uses X-ray beams, composed of highly-energetic photons. The image reconstruction from X-ray measurements is based on the Radon transform; see the books by Frank Natterer on the subject.SPECT (Single Photon Emission Computed [or Computerized] Tomography) is an inverse source problem. One is interested in reconstructing the spatial distribution of a source of radiation from boundary measurements. Mathematically, because the photons are absorbed by human tissues before they can be measured, one has to invert an attenuated Radon transform . Exact inversion formulas have only obtained very recently and independently by A.L. Bukhgeim and collaborators using the technique of A-analytic functions and by R.G. Novikov using techniques borrowed from inverse scattering. I have worked on extension of the latter work for more general source terms (with applications in Doppler tomography for instance) and for incomplete angular measurements. See the following paper On the attenuated Radon transform with full and partial measurements. An extension to scattering problems may be found in the joint paper with A. Tamasan: Inverse source problems in transport equations. One of the main advantages of explicit inversion formulas is that they allow us to construct fast inversion algorithms. With Philippe Moireau, we have generalized the Fast Slant Stack method to the inversion of the attenuated Radon transform with full or partial measurements. See the following paper: Fast numerical inversion of the attenuated Radon transform with full and partial measurements.

Ray transforms also appear in geophysical imaging. The main difference with respect to most imaging techniques is that rays are now curved. In the simplified (yet practically useful) case where the rays are the geodesics of a hyperbolic metric, I have extended the explicit formulas obtained in Euclidean geometry to the scalar and vectorial source problem in hyperbolic geometry; see the paper: Ray Transforms in Hyperbolic Geometry.

Ray transforms also find applications in the reconstruction of concentration profiles in the atmosphere. In the non-scattering framework, frequency-dependent radiation emitted by different gases may be measured by satellites. In the one-dimensional setting, there is only one ray (radiation moves up). The z-dependent concentration profiles may thus be reconstructed from the frequency dependency in the measurements. Unlike the ray transform problems mentioned above, the concentration profile reconstruction is a severely ill-posed problem (so that noise is severely amplified during the reconstruction process). With Kui Ren, we show this and provide methods to recover thin layers with sharp contrast (dust layers or ozone layers) in the following paper Atmospheric Concentration Profile Reconstructions from Radiation Measurements.

Here is a presentation I gave at IPAM in the fall of 2003 on SPECT problems.

Optical Tomography.

Optical tomography (OT) uses near infra red (NIR) photons to probe human tissues. NIR photons are very low energy and thus are quite harmless. The corollary of their low energy is that they scatter a lot with human tissues, which significantly reduces their use in medical imaging. Despite its relatively poor spatial resolution, OT has a however great advantage: it can image tissue properties (such as absorption) that other imaging techniques cannot do.Motivated by works by S. Arridge, I have worked on the modeling of photon propagation in domains that are highly scattering everywhere except in small-volume non-scattering layers. The understanding of such domains is important if photons are to be used to image properties of the human head.

With Kui Ren, we have shown that a macroscopic (hence computationally cheap) generalized diffusion equation including singular interfaces could be used to model such a propagation; see Generalized diffusion model in optical tomography with clear layers . A theoretical and numerical analysis of such models can also be found in the papers Transport through diffusive and non-diffusive regions, embedded objects, and clear layers and Particle transport through scattering regions with clear layers and inclusions . Once the clear layers have been modeled by singular interfaces, it remains an interesting problem to understand whether they (and the other relevant physical parameters involved) can be reconstructed from boundary measurements. Some answers are provided in the paper Reconstructions in impedance and optical tomography with singular interfaces. The latter paper adapts to singular layers the factorization method developed by A. Kirsch .

Inverse Problems in OT are known to be extremely ill-posed, with an error in the reconstruction of the diffusion and absorption properties logarithmic in the error level on the measured data (in the sense that an accuracy of 10E-10 in the data may result in an accuracy of 1/10 in the reconstruction). Here is a way to somewhat overcome this stability constraint by using asymptotic expansions of small volume inclusions. Another promising approach to increase the amount of available data is to use time harmonic sources. The following paper in collaboration with with K. Ren and A. Hielscher deals with this issue: Frequency Domain Optical Tomography Based on the Equation of Radiative Transfer. In that paper, we show that increasing the source modulation frequency improves the reconstruction of the optial coefficients. Theoretical explanations based on careful stationary phase analyses can be found in the two papers: Angular average of time-harmonic transport solutions (with A.Jollivet, I.Langmore, and F.Monard) Comm. Partial Differential Equations, 36(6), pp. 1044-1070, 2011; and Inverse Transport with isotropic time harmonic sources (with F. Monard), SIAM J. Math. Anal., 2012.